AI's Lifeline: Boosting Productivity and Filling Labor Gaps in a Shrinking, Aging World

Bernie is trying to shoot his future carer when no human substitute exists

The global economic order is currently confronting a structural transformation defined by the simultaneous acceleration of demographic inversion and the rapid institutionalization of artificial intelligence (AI). It is important to consider these factors side by side, otherwise it distorts our view of the future>

For decades, Western economies relied on a demographic dividend characterized by an expanding, youthful workforce that stimulated both production and consumption. This was a constant in our economic outlook.

In the 21st century, this dividend has transitioned into a persistent demographic drag. In most advanced economies, the working-age population is contracting while the old-age dependency ratio, the proportion of seniors to those of working age, is reaching unprecedented heights.

This shift creates a labour-market vacuum that threatens the long-term viability of gross domestic product (GDP) growth and fiscal stability.

Simultaneously, AI has emerged not merely as an incremental tool for efficiency, but as a general-purpose technology, capable of reconfiguring the very nature of productive capacity.

While traditional narratives surrounding automation focus on the displacement of existing human labour, the unique conditions of ageing economies suggest a more nuanced paradigm: AI as compensatory capacity.

In this framework, AI serves as a substitute for “non-existent workers”, those individuals lost to retirement and declining birth rates who cannot be replaced by the current demographic pipeline.

Does AI represent the obsolescence of humans or a needed trend to cover a supply-side demand that we have no workers for anyway?.

The following analysis explores the interaction between these forces and examines how AI-driven productivity gains may mitigate demographic decline and redefine macroeconomic stability in the Western world.

The Demographic Precipice: Structural Workforce Contraction

The demographic landscape across the OECD is undergoing a fundamental shift that is both predictable and irreversible.

Increasing life expectancy, while a significant social achievement, is occurring alongside persistently low fertility rates that remain well below the replacement level of 2.1 births per woman in most member states.

The result is a dual pressure: a shrinking base of young entrants into the labour market and a swelling cohort of retirees requiring support.

Regional Projections and the Working-Age Peak

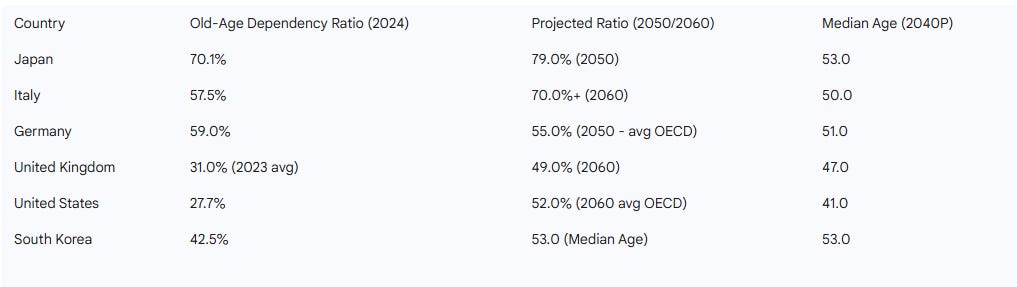

Data indicate that the working-age population (ages 20-64) across the OECD will decline by an average of 8% by 2060. However, this average masks extreme variations. Approximately one-quarter of member states will face contractions exceeding 30%. Japan remains the global pioneer of this “super-ageing” trend, with its working-age population having fallen by 16% from its 1995 peak of 87.3 million to 73.7 million in 2024. By 2050, the Japanese workforce is projected to be only 60% of its original size.

This means we should be thoughtful before predicting an employment armageddon; there is a case to be made that AI/robotics may provide the care to aging populations that would otherwise be impossible.

In Europe, the situation is similarly acute. In 2025, 22 of the 25 countries with the highest proportions of seniors are European, led by nations like Italy, Greece, and Germany. Even in the United States, which has historically benefited from higher birth rates and migration, the U.S.-born working-age population is forecast to shrink every year for the next decade. Without sustained immigration, achieving historically “normal” GDP growth rates in the U.S. will become statistically impossible.

I can argue whether immigration or robotics is the correct compensatory policy, we can’t argue that we have a labor gap that needs to be filled

The old-age dependency ratio, defined as the number of individuals aged 65 or older per 100 people of working age, has already risen dramatically from 19% in 1980 to 31% in 2023. By 2060, this ratio is projected to hit 52% across the OECD.

This implies that the burden of toil on each worker will effectively double, as they must produce enough to sustain themselves and contribute roughly 50% of the income required for one retired individual.

The idea that we can do this, resourced from current demographic assumptions, is clearly delusional; society must cure this situation either through immigration or robotics, or some other hybrid of both .

The Productivity Imperative for Fiscal Sustainability

The decline in the employment-to-population ratio is a rational threat to living standards.

OECD estimates suggest that if labour productivity growth remains unchanged, per capita GDP growth could collapse by 40%, falling from an annual rate of 1.0% during 2006–2019 to just 0.6% between 2024 and 2060.

This slowdown is driven by two primary factors: fewer productive hours worked in the aggregate and the diversion of national income toward non-productive social expenditures.

Public spending on pensions and health is projected to rise by 3% of GDP across the OECD.

In economies like Australia, where personal income tax revenue accounts for 51.6% of total revenue, more than double the OECD average, the shrinkage of the workforce creates a fiscal guillotine where revenue falls just as mandatory expenditures for the elderly soar.

Only by boosting productivity growth can these countries maintain a growth level close to past levels and avoid a generational wealth crisis. There is no other pathway to productivity growth than AI and robotics.

Folks should be really careful about what they rally against because you might be well objecting to a solution to a problem that youve not yet comprehended.

The Macroeconomics of AI-Driven Productivity

Artificial intelligence is positioned as the primary mechanism for counteracting demographic headwinds. Unlike previous waves of automation that targeted routine manual tasks, generative AI is a general-purpose technology capable of automating non-routine cognitive and decision-making functions.

This distinction is critical because Western economies are overwhelmingly service-based and rely heavily on knowledge workers who were previously shielded from technological disruption.

Quantifying the AI Productivity Bonus

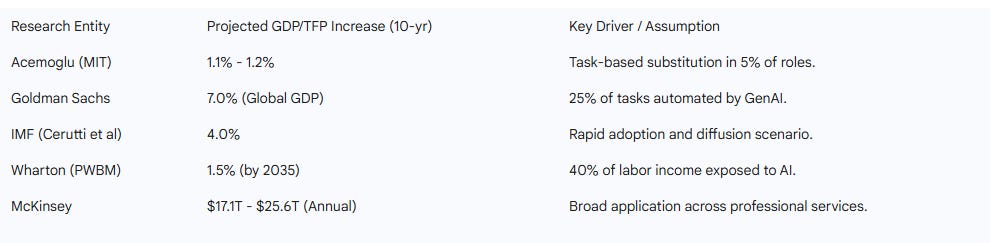

Economists offer a wide range of estimates regarding the total factor productivity (TFP) boost provided by AI. Conservative models, such as that of Daron Acemoglu (2024), project that AI will increase US GDP by a modest 1.1% to 1.2% over the next decade, representing an annualized increase of approximately 0.1 percentage points. Acemoglu’s caution stems from the estimate that only 5% of tasks will be profitably automated within 10 years, as AI begins to tackle “hard tasks” such as complex medical diagnosis and nuanced legal judgment.

In contrast, more optimistic forecasts from Goldman Sachs suggest that generative AI could automate 25% of all work tasks, leading to a 7% increase in global GDP (roughly $7 trillion) and a 15% increase in labour productivity. The Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM) provides a middle ground, estimating that AI will increase productivity and GDP by 1.5% by 2035 and 3.7% by 2075.

The PWBM preliminary analysis further suggests that AI could reduce federal deficits by $400 billion between 2026 and 2035, primarily through cost savings in government administration and increased tax receipts from a more efficient private sector. These gains, while significant, follow the “J-curve” logic of productivity: an initial latency period of investment and reorganization precedes the aggregate benefits as the technology diffuses through the economy.

Clearly, the potential exists for AI to reduce government spending in a time where worker’ access is shrinking.

If we haven’t got the folk to supply labour to these government jobs, then we shouldn't fear a government worker productivity benefit.

Reframing Value: Total Productive Capacity (TPC)

A fundamental shift in economic analysis is required to understand AI in ageing societies.

Traditional “labour-centric” narratives are increasingly ill-fitted for an era where intelligent systems introduce large-scale adaptive cognition. The “Total Productive Capacity” (TPC) framework argues that the economic focus should shift from substituting human labour to expanding the output potential of a particular socio-technical stack.

In this conceptualization, AI is an infrastructural innovation that extends a system’s capacity to coordinate, predict, and decide well before that capacity is statistically visible in traditional labour metrics. For an ageing economy, this means AI can maintain “Total Productive Capacity” even as the “Labour Component” of that capacity shrinks.

Thus, AI breaks the classical growth theory assumption that labour is the main binding constraint on output.

As with most of my work, I challenge orthodox economic models and the way they project the future using assumptions that fail to hold under structural change.

AI as Labour Substitution for Non-Existent Workers

Determining whether AI functions as displacement (replacing an existing worker) or substitution (filling a vacancy that cannot be otherwise filled) is best considered in the context of sectoral shortages. In several critical Western industries, the labour supply has already collapsed below the level required for basic service continuity.

The economy is taking on water and band keeps playing the same old tunes not noticing the water on our ankles

The Crisis in Healthcare and Aged Care

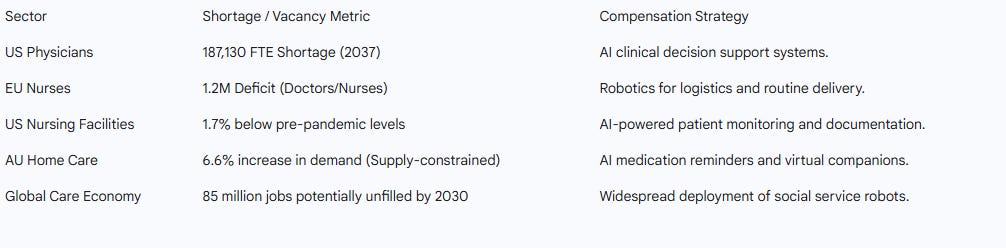

The healthcare sector is the epicenter of the “non-existent worker” crisis.

As the population aged 80 and over is projected to grow by 2.5 times between 2022 and 2060, demand for geriatric care is soaring. Simultaneously, the healthcare workforce is itself ageing. In the European Union, over one-third of doctors and a quarter of nurses are over age 55 and expected to retire shortly. The EU faced a health workforce deficit of 1.2 million professionals in 2022.

In the United States, the American Hospital Association estimates that the ratio of workers per senior will drop to just 2.9 by 2030. Projections from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) indicate a shortage of 187,130 full-time equivalent physicians by 2037. This is compounded by a high “intent to leave” among existing staff; 41% of nurses indicate they plan to exit the profession within two years due to burnout and stress.

We open our eyes and look at the actual data. Meme-based rationalism pulls thinking in every direction, untethered from constraint. The facts anchor us. They define the boundary conditions and narrow the range of outcomes. Once you accept the physical inputs, capital intensity, energy load, workforce limits, and supply chains, the future stops being abstract. It becomes a sequence of conditions unfolding from what already exists.

AI and robotics in this sector act as a compensatory capacity. Robots like the TUG are delivering medications and supplies, freeing human nurses to focus on clinical judgment. In nursing homes, robots are being used for the physical tasks, such as lifting patients, which typically cause back and knee injuries, leading to higher employee retention and the ability to employ less physically robust workers.

Knowledge Preservation in Utilities and Infrastructure

Infrastructure sectors, including water and power, are facing a “Great Retirement” that threatens institutional knowledge. The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that nearly 25% of the current utility workforce will be eligible to retire within 5 years. These workers possess “sixth sense” pattern recognition—the ability to hear equipment drift or identify parameter drift based on decades of field experience.

Traditional handover binders are often useless for the complex judgment calls these experts make daily. AI-powered SaaS solutions and digital twins are now being used to capture this unwritten expertise.

By training AI on historical investigation reports, approval decisions, and sensor data, utilities are creating “expert models” that guide new hires through investigations the way a seasoned veteran would. In the water sector, AI like CivilSense is being used to condense years of operational expertise into actionable guidance for teams with limited direct experience.

Administrative Offloading in Education

The global education sector is characterized by high burnout and attrition. In the UK, 84% of teachers report negative mental health impacts due to workload. Over half of UK teachers have considered leaving the profession in the last 12 months, specifically due to the marking workload.

AI in education is increasingly focused on “workload reduction” rather than “teacher replacement”. Studies show that daily AI use can save teachers an average of 70 minutes per week, or 45 hours per year. AI-powered platforms can mark essay sets in under two minutes and generate inspection-ready reporting. This reclamation of capacity is a substitute for the support staff and teaching assistants who are increasingly absent due to recruitment difficulties.

AI shifts the teacher–student framework from batch instruction to continuous feedback.

Instead of one-to-many delivery followed by delayed marking, students interact with adaptive systems that respond in real time, surface misconceptions immediately, and adjust difficulty dynamically.

The teacher moves from primary content transmitter to supervisor of learning architecture, auditing outputs, refining prompts, and targeting intervention where human judgement adds value.

Assessment becomes iterative rather than episodic. Administrative load compresses, while personalisation expands. In that structure, scale no longer depends on adding staff; it depends on computing, oversight, and discipline in curriculum design.

A parallel narrative claims AI erodes cognitive capacity, and that meme has captured much of the discussion. It overlooks how tools have always extended human capability when used with structure and intent.

Calculators did not eliminate mathematics; they shifted effort toward higher-order reasoning. AI functions the same way. Used properly, it compresses low-value friction and elevates drafting, feedback, translation, and access to expertise. In regions with limited access to qualified teachers, tutors, or updated materials, AI can provide baseline instruction, language support, and exam preparation at near-zero marginal cost.

The standard rises not because thinking disappears, but because more people gain access to structured guidance and iterative improvement.

Macroeconomic Dynamics: Deflation, Demand, and Equilibrium

The interaction between AI productivity and demographic supply constraints creates a unique macroeconomic environment where traditional rules of inflation and deflation are challenged. In an ageing society, the labor shortage acts as a supply-side shock that is typically inflationary, while AI’s productivity gains act as a supply expansion that is typically disinflationary.

The Disinflationary Potential of AI

AI is modeled as a permanent increase in productivity that differs by sector. In a scenario where households and firms do not anticipate the full boost to productivity (the “unanticipated case”), AI adoption is initially disinflationary because it expands the economy’s production frontier faster than aggregate demand can respond.

Growth-driven deflation” is uncommon but historically consequential. It emerges when productivity expands faster than demand, lowering unit costs while output rises. Episodes in the late 19th century, during rapid industrialisation and electrification, and again in the late 1990s, though minor comparatively, through digitisation and network computing, illustrate how supply-side gains can compress prices while real growth accelerates.

If AI adoption is “anticipated” and firms begin front-loading investment, (which they are ), the immediate effect can be inflationary as demand for chips, data centers, and electricity outstrips immediate supply.

The Shift from Demand-Constrained to Supply-Constrained Growth

The global economy has shifted from a demand-constrained regime to a supply-constrained one. The binding variable is no longer consumer appetite or credit expansion, but access to energy, metals, components, and processing capacity. Materials denial now functions as a structural feature of the system. Critical inputs such as copper, rare earths, advanced semiconductors, and refined fuels are concentrated within specific jurisdictions and subject to export controls, licensing regimes, and strategic stockpiling.

Capacity cannot be expanded quickly; mines, smelters, fabs, and grids require years of capital formation. In this environment, growth is gated by throughput. Capital allocation, industrial policy, and geopolitical alignment determine who secures material flow and who absorbs constraint.

Bluntly, you can’t build the robot armies that will displace humans, we dont have the materials

In the previous decade, excess capacity and weak demand kept inflation low. Today, ageing populations in economies representing 75% of global output mean that supply elasticity has plummeted. Fewer workers are caring for more seniors, raising the cost of non-tradable services like health and elder care, a phenomenon known as the Baumol Effect.

The Baumol Effect describes what happens when wages rise across an economy even though productivity growth is uneven between sectors.

Some industries, such as manufacturing or technology, increase productivity quickly. A factory that once needed 100 workers might later produce more output with 20 because of automation. Output per worker rises.

Other sectors, such as education, healthcare, live performance, or aged care, do not scale the same way. A teacher still teaches roughly the same number of students per class. A string quartet still requires four musicians to perform a piece written in 1800. Output per worker barely changes.

However, wages across the economy tend to move together. If manufacturing workers earn more because productivity increased, schools and hospitals must also raise wages to compete for labour. Even if productivity in those sectors has not improved, their wage costs rise.

The result:

• Labour-intensive services become more expensive over time

• The share of GDP devoted to services rises

• Cost pressure builds in sectors that cannot automate easily

This is why healthcare, education, and care work often experience persistent cost inflation even when goods prices fall.

AI potentially shifts parts of education, law, and administration out of the “low productivity” bucket. If AI meaningfully increases output per worker in those sectors, it dampens the Baumol cost pressure. If it fails to scale physically due to energy or materials constraints, the cost disease persists.

AI represents the “best chance” to relax these supply-side constraints.

By producing a major sustained surge in productivity, AI enables the expansion of the economy’s supply capacity that demographic trends would otherwise suppress. Without this intervention, Western economies would face a future of subdued growth and persistent inflationary pressure from soaring labour costs.

Occupational Mix and the Skill Transformation

The “Tsunami” of AI is not expected to cause mass unemployment but rather a rapid transformation of the demand for skills. This is particularly evident in the shifting occupational mix of Western economies since the release of ChatGPT.

Historical Comparison of Occupational Shifts

While fears of AI-driven cognitive erosion are high, the actual dissimilarity in the occupational mix 33 months after the release of ChatGPT is only about 1 percentage point higher than the trend observed during the adoption of the internet in 1996.

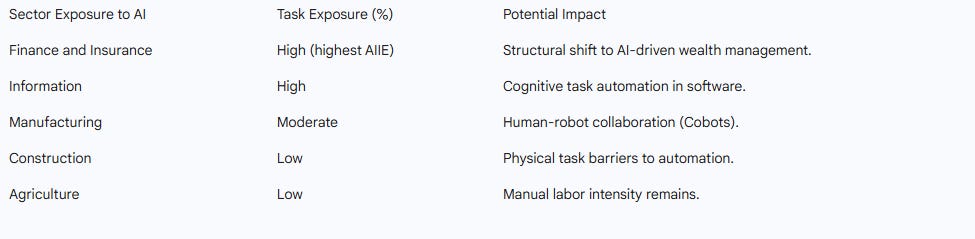

The larger shifts are currently concentrated in the Information, Financial Activities, and professional services sectors.

Crucially, measures of AI exposure show no relationship with changes in unemployment. Unemployed workers continue to come from occupations with 25% to 35% task exposure, a figure that has remained steady since AI’s introduction.

This supports the hypothesis that current labour market changes are more indicative of adjustment than displacement.

The Polarization of Wages and the “AI Penalization”

While AI boosts productivity, its impact on compensation is contested. High-skilled workers with AI “capital” experience greater opportunities and significant wage premiums. Vacancies requiring AI skills offer an 11% higher salary within the same firm and a 5% premium for the same job title.

However, a psychological “AI penalization” effect has been documented: in some contexts, people reduce compensation for AI-assisted workers because they believe these workers deserve less credit for their output.

Furthermore, the spread of “surveillance pay” or “algorithmic wage discrimination”, where opaque systems set compensation based on real-time data collection, threatens to decouple hard work from fair pay in sectors like healthcare and logistics.

Sectoral Maturity and the Deployment Timeline

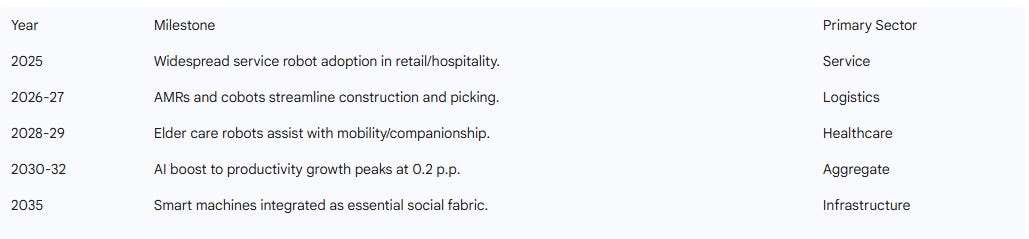

The realization of AI as compensatory capacity depends on the technical maturity of robotics and agentic systems. The decade from 2025 to 2035 is projected to be the “Decade of mass integration”.

Industrial and Service Robotics (2025-2030)

By 2025, physical AI, the fusion of AI with robotics, is expected to see widespread adoption. Early adopters like Foxconn and Amazon have already seen digital twin simulations cut deployment times by 40%. In logistics, Autonomous Mobile Robots (AMRs) are streamlining warehouse picking and last-mile delivery.

In 2026-2027, robots are expected to become permanent fixtures in large office buildings and smart campuses, handling concierge and navigation tasks. By 2028-2029, household integration will scale up, with elder care robotics becoming standard for mobility assistance and medication reminders in ageing societies like Japan and Europe.

Again, this is highly dependent on whether the materials capacity can keep up with deployment.

Smart Machines and Infrastructure (2030-2035)

By 2035, semi-autonomous systems are expected to be ubiquitous and “hiding in plain sight”. In hospitals, they will handle mundane chores to free up doctors for patient time. In the energy sector, AI agents will manage grid stability autonomously, predicting demand fluctuations and optimizing renewable energy distribution in real-time.

The UK’s “Smart Machines Strategy 2035” estimates that if fully adopted, these technologies could increase UK Gross Value Added (GVA) from £6.4 billion to £150 billion by 2035, driven by reduced costs and the creation of new industries.

Global Divergence: The AI Divide

The interaction of AI and demographics is likely to exacerbate cross-country income inequality. Advanced economies have the highest exposure to AI, about 60% of jobs compared to 26% in low-income countries, because their economies are more concentrated in cognitive-intensive roles. Aging demographics and a slower rollout due to material constraints slow everything anyway.

Advanced Economies vs. EMDEs

Advanced economies are better positioned to harness AI due to superior digital infrastructure, innovation capacity, and clear regulatory frameworks. The United States, for example, boasts more data centers than the next 15 countries combined. Furthermore, AEs have the strongest positional advantage in the “chip war,” controlling access to high-end semiconductors and capital.

In contrast, Emerging Market and Developing Economies face a “double hit.” They are less affected by the immediate productivity boost because their production structures are concentrated in low-exposure sectors like agriculture, and they are less prepared to adopt new technologies. This creates a risk of a divergence , where the benefits of AI remain concentrated in a handful of wealthy nations.

The Demographic Pivot in EMDEs

While the West shrinks, Africa and parts of South Asia will continue to see youthful population growth. By 2040, Africa will be the only region with a growing working-age population, requiring the creation of 2 million jobs per month to absorb new entrants. A critical question for global stability is whether the “non-existent worker” vacancies in Asia and the West can be bridged by human labour from Africa, or if AI will fill those roles, potentially stranding billions of young people in the global south with limited economic mobility.

Policy Imperatives for the Ageing AI Economy

The success of the transition to an AI-augmented ageing economy depends on proactive policy design.

Promoting Active Ageing and Mobility

Facilitating the continued participation of healthy older individuals is essential. Raising older-age employment to the levels of the highest-performing OECD countries could add 0.2 to 0.4 percentage points to annual per capita GDP growth. This requires flexible retirement pathways and significant investment in lifelong learning; currently, only one-third of adults aged 60-65 participate in training, compared to over half of those aged 25-44.

Active Labour Market Policies must be redesigned to facilitate transition from AI-displaced roles to sectors facing demographic shortages. Japan’s experience shows that while participation rates among women and seniors have increased, they often involve shorter hours, partly due to policy disincentives, such as income thresholds for pension eligibility.

Directing Innovation Toward Social Value

Innovation must be steered toward high-value tasks, particularly in health, energy, and education. Governments can play a role in bootstrapping community development of smart machine modular simulation and hardware tools, as outlined in the UK’s strategy.

Furthermore, as the capital share of income rises relative to labour due to AI, policymakers must address the distributional consequences. This includes upgrading regulatory frameworks to prevent exclusionary “data moats” and ensuring that productivity gains are shared widely to maintain consumer demand and social cohesion.

Synthesis and Conclusion

The demographic inversion of Western economies creates an absolute limit on human labour that traditional capital investment cannot overcome.

The evidence suggests that the primary macroeconomic role of AI in the coming decades will be as a compensatory capacity, a technical replacement for a human workforce that is no longer present.

Key Analytical Findings

Workforce Contraction as the Prime Mover: The 8% decline in OECD working-age population by 2060, and the collapse of per capita GDP growth by 40%, make the status quo untenable.

AI as Infrastructure for Continuity: In healthcare (1.2M vacancies), utilities (25% retirements), and infrastructure, AI is not displacing workers but ensuring service continuity when human labour is unavailable.

The Productivity Offset: AI-driven TFP gains, estimated at 0.5% to 1.5% in the medium term, are critical for maintaining fiscal sustainability as ageing-related spending rises by 3% of GDP.

Supply-Side Rebalancing: AI relaxes the supply-side constraints caused by demographic drag, potentially preventing a permanent shift into a high-inflation, low-growth regime.

Adaptive Capacity as the Shield: High AI exposure is currently correlated with high adaptive capacity, suggesting that the most “disrupted” workers are also those best equipped to pivot to new high-complementarity roles.

In conclusion, the pairing of AI and demographics represents a historical pivot from a demand-constrained global economy to a supply-constrained one.

AI’s function as labour substitution for non-existent workers is the essential mechanism for preventing structural economic stagnation.

Bernie Sanders and his comrades are objecting to the trend that will benefit aging populations, where there is currently no other mechanism to look after the elderly because of our aging demographics.

However, the benefits of this transition are not guaranteed and are likely to be unevenly distributed between advanced and emerging economies. This is no different to any other era in technology substitution.

The silver lining of the silver economy will only be realized if Western societies proactively invest in human-AI complementarity, lifelong learning, and the regulatory frameworks necessary to ensure that technological gains are translated into broad-based social prosperity.

Thanks for some really engaging and insightful Saturday morning reading!

On this point:

By 2028-2029, household integration will scale up, with elder care robotics becoming standard for mobility assistance and medication reminders in ageing societies like Japan and Europe.

I do hope it’s true, but I wonder how fast it will happen. My 86-year-old father was recently in the hospital and then rehab after a fall. There was not a single robot to be seen. His care was handled by many, many humans.

Are you aware of Japanese or European organizations pushing forward with this?

About the Baumol effect - if large-scale deployment of AI in knowledge work sectors results in fewer hires and possibly decreased wages that would actually work counter to the way Baumol and Bowen outlined it? Where wage increases in higher productivity sectors draw low productivity sector wages up too?

Regardless, it still seems to me that service sector inflation is very likely even if AI brings about deflation in other sectors.

And, your point about whether we’ll have the materials we need to make robots is really important.

This is an area where the fear of a rising age dependency ratio seems a little unnecessary. Japan has changed its population by 16% while steadily increasing its gdp per capita. Many African countries now have youth and old-age dependency ratio well above 100%.

I'd suggest that neither AI or immigration are the solution as one is unpredictable and the other already being widely rejected. Adaptation probably will occur - people will do with less, societies will prioritize and human ingenuity will triumph.